Deep within every piece of magnetic material, electrons dance to the invisible tune of quantum mechanics. Their spins, akin to tiny atomic tops, dictate the magnetic behavior of the material they inhabit. This microscopic ballet is the cornerstone of magnetic phenomena, and it's these spins that a team of JILA researchers—headed by JILA Fellows and University of Colorado Boulder physics professors Margaret Murnane and Henry Kapteyn—has learned to control with remarkable precision, potentially redefining the future of electronics and data storage.

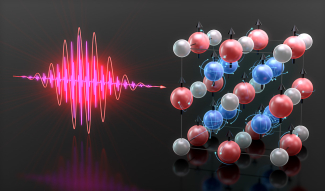

As reported in a new Science Advances paper, the JILA team and collaborators from universities in Sweden, Greece, and Germany probed the spin dynamics within a special material known as a Heusler compound: a mixture of metals that behaves like a single magnetic material. For this study, the researchers utilized a compound of cobalt, manganese, and gallium, which behaved as a conductor for electrons whose spins were aligned upwards and as an insulator for electrons whose spins were aligned downwards.

Using a form of light called extreme ultraviolet high-harmonic generation (EUV HHG) as a probe, the researchers could track the re-orientations of the spins inside the compound after exciting it with a femtosecond laser, which caused the sample to change its magnetic properties. The key to accurately interpreting the spin re-orientations was the ability to tune the color of the EUV HHG probe light.

“In the past, people haven't done this color tuning of HHG,” explained co-first author and JILA graduate student Sinéad Ryan. “Usually, scientists only measured the signal at a few different colors, maybe one or two per magnetic element at most.” In a historic first, the JILA team tuned their EUV light probe across the magnetic resonances of each element within the compound to track the spin changes with a precision down to femtoseconds (a quadrillionth of a second).

“On top of that, we also changed the laser excitation fluence, so we were changing how much power we used to manipulate the spins,” Ryan elaborated, highlighting that that step was also an experimental first for this type of research. By changing the power, the researchers could influence the spin changes within the compound.

Using their novel approach, the researchers collaborated with theorist and co-first author Mohamed Elhanoty of Uppsala University, who visited JILA, to compare theoretical models of spin changes to their experimental data. Their results showed strong correspondence between data and theory. “We felt that we'd set a new standard with the agreement between the theory and the experiment,” added Ryan.

Fine Tuning Light Energy

To dive into the spin dynamics of their Heusler compound, the researchers brought an innovative tool to the table: extreme ultraviolet high-harmonic probes. To produce the probes, the researchers focused 800-nanometer laser light into a tube filled with neon gas, where the laser's electric field pulled the electrons away from their atoms and then pushed them back. When the electrons snapped back, they acted like rubber bands released after being stretched, creating purple bursts of light at a higher frequency (and energy) than the laser that kicked them out. Ryan tuned these bursts to resonate with the energies of the cobalt and the manganese within the sample, measuring element-specific spin dynamics and magnetic behaviors within the material that the team could further manipulate.

A Competition of Spin Effects

In their experiment, the researchers found that by tuning the power of the excitation laser and the color (or the photon energy) of their EUV probe, they could determine which spin effects were dominant at different times within their compound. They compared their measurements to a complex computational model called time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT). This model predicts how a cloud of electrons in a material will evolve from moment to moment when exposed to various inputs.

Using the TD-DFT framework, Elhanoty found agreement between the model and the experimental data due to competing spin effects within the Heusler compound: spin flips up or down and spin transfers. The spin flips happen within one element in the sample as the spins shift their orientation from up to down and vice versa. In contrast, spin transfers happen within multiple elements, in this case, cobalt and manganese, as they transfer spins between each other, causing each material to become more or less magnetic as time progresses. “What he [Elhanoty] found in the theory was that the spin flips were quite dominant on early timescales, and then the spin transfers became more dominant,” explained Ryan. “Then, as time progressed, more de-magnetization effects take over, and the sample de-magnetizes.”

Designing More Efficient Materials

Understanding which effects were dominant at which energy levels and times allowed the researchers to understand better how spins could be manipulated to give materials more powerful magnetic and electronic properties.

“There’s this concept of spintronics, which takes the electronics that we currently have, and instead of using only the electron’s charge, we also use the electron’s spin,” elaborated Ryan. “So, spintronics also have a magnetic component. Using spin instead of electronic charge could create devices with less resistance and less thermal heating, making devices faster and more efficient.”

From their work with Elhanoty and their other collaborators, the JILA team gained a deeper insight into spin dynamics within Heusler compounds. Ryan said: “It was really rewarding to see such a good agreement with the theory and experiment when it came from this really close and productive collaboration as well.” The JILA researchers are hopeful to continue this collaboration in studying other compounds to understand better how light can be used to manipulate spin patterns.

Written by Kenna Hughes-Castleberry, JILA Science Communicator